Why Is Global Finance Stacked Against Young Countries?

Imagine playing a game where the rules were written decades before you were born – and they’re stacked against you.

This is how many young countries (nations where 50-80% of the population is under 30) feel about today’s global financial system. The world’s financial architecture was largely designed by high-income countries last century, and they still call most of the shots. Meanwhile, countries full of young people often struggle to get affordable loans and are struggling with global debt.

Below, we break down why the system is outdated, how it traps “young” nations in debt, real examples of the consequences, and what we can do about it.

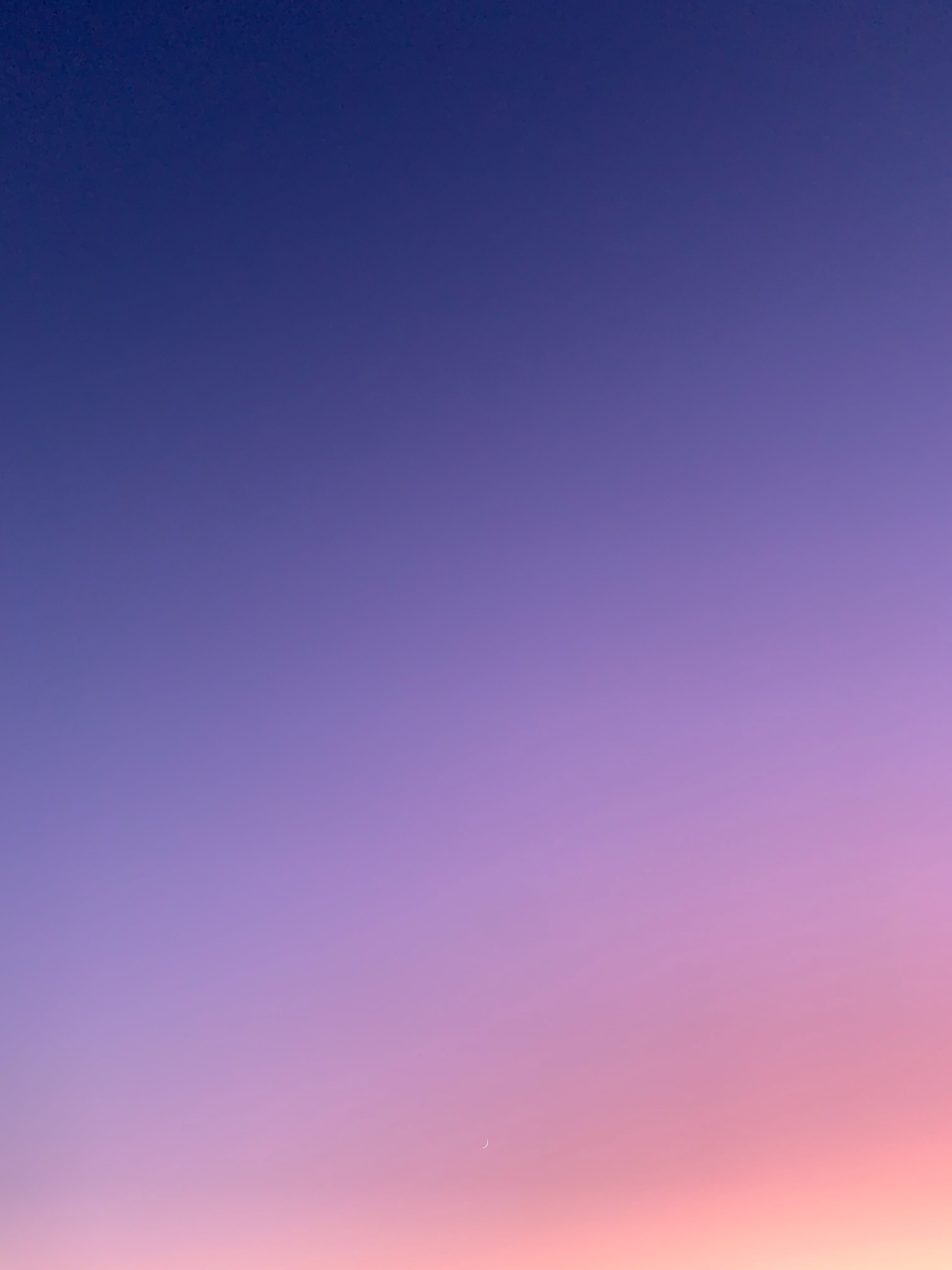

This map is based on 2024 UN Demographic Data, with a margin of error of 2-5% for countries with well-established civil registration systems and 5-10% for those with limited standards.

This map is based on 2024 UN Demographic Data, with a margin of error of 2-5% for countries with well-established civil registration systems and 5-10% for those with limited standards.

An Outdated Power Structure Dominated by Rich Countries

The international financial system – including the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank – is built on a post-World War II power structure.

These developed economies have far more voting power in global financial institutions than their share of the world’s population. For example, the G7 holds over 40% of IMF voting shares, giving it an effective veto on major decisions, while all 67 of the world's of the world's most climate-vulnerable (and mostly low-income) countries combined have just 6.7%. Major European economies also collectively hold enough votes to block changes. In contrast, Africa, Asia, and Latin America – home to most of the world's young people – remain underrepresented. Many in the Global South have called such measures out as outdated and prevents young, developing countries from having more say in decisions about international loans, debt relief, and economic policy.

The result? Many have suggested that policies on debt, aid, and finance often prioritize the stability of global markets or creditor rights (i.e. making sure rich lenders get paid back) over the needs of young countries trying to invest in health, education, and jobs for their people. This power imbalance leaves many young countries feeling that the financial system isn’t designed for them – it’s rigged in favor of its original architects.

Young Countries Struggle to Finance Their Future

Many young, developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia have a median age under 30.

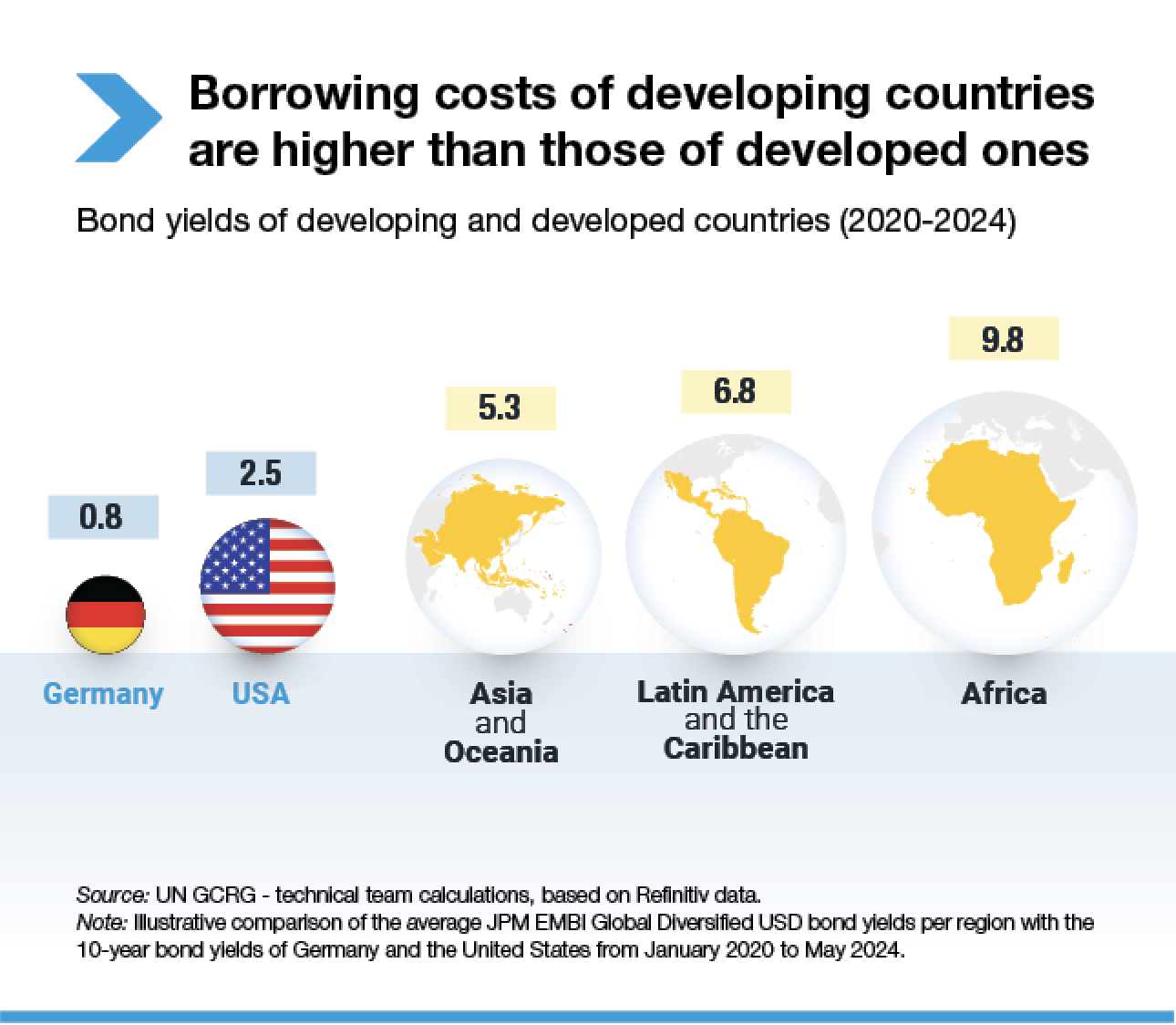

These “young countries” have enormous potential – a huge generation of young leaders, workers, and entrepreneurs – but also enormous needs. They need to build schools, hospitals, infrastructure, and create jobs at a record pace to keep up with their growing populations. Yet, when these countries seek financing to invest in development, they face sky-high costs and barriers. Global credit markets treat them as risky, so they are charged much higher interest rates than rich countries. Most of these youthful nations , often pay a premium to borrow money that countries in Europe or North America would never accept.

Average international borrowing costs are far higher for young, developing regions (e.g. nearly 10% in Africa) than for aging, developed nations. In practice, this means a country like Kenya or Bangladesh might have to offer 8-10% interest on its bonds, when developed countries can borrow at much lower.

That huge gap isn’t because young countries are irresponsible – often it’s because of biases in the global financial system. Credit rating agencies (mostly based in the Global North) often give young, developing countries lower ratings than the economic data seems to warrant. Investors, in turn, demand higher interest to compensate for perceived risk, even if the actual risk of default isn’t that high. A United Nations study found that subjective “risk perception” by ratings agencies added an extra $75 billion in costs to African countries – money that wouldn’t have been spent if they were judged purely by the numbers. African nations sometimes pay almost 6 percentage points more in interest than other countries with the same credit rating, due to this perception penalty.

Paying such unfair borrowing costs has real consequences. Governments end up spending a huge chunk of their budgets just to repay loans (plus interest), leaving little left to invest in youth programs, jobs, or services. In 2023, a record 54 young, developing countries (home to 3.3 billion people, almost half of the world) spent over 10% of their revenues just on interest payments, often more on debt than on education or health for their citizens. This is a vicious cycle: high interest costs lead to more borrowing to plug budget holes, which leads to even higher debt. Many young countries thus find themselves trapped in unsustainable debt cycles – borrowing just to pay off old debts, while new generations see few tangible improvements. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres bluntly stated, “financing is failing the developing world” .

Debt and Distress: Country Examples

These challenges aren’t just abstract concepts – they’re affecting real countries and young people’s lives right now. Here are just a few examples of how the global finance game is stacked against young countries:

Nigeria

Africa’s most populous country (median age is 18) is grappling with a debt crisis despite its oil wealth. In 2022, Nigeria used 96% of its government revenue just to service debt – nearly every dollar earned went to creditors. This left very little for investing in schools, healthcare or infrastructure. With such a high debt burden, the future of Nigeria’s large youth population hangs in the balance.

Pakistan

Pakistan has over 240 million people (median age is 22) and it has faced repeated financial crunches. For the fiscal year 2023-24, Pakistan needed over $22 billion to repay external debt and interest. The country has requested IMF bailouts 22 times in the past 40 years. Each crisis brings tough measures like devaluing the currency and cutting public spending – actions that hit young people the hardest through higher prices and fewer jobs.

Lebanon

Once a middle-income country, Lebanon (median age is 30) spiraled into one of the worst economic collapses in modern history after defaulting on its foreign debt in 2020. Its credit rating sank low as past borrowing caught up. The default shattered the banking system; the currency lost over 90% of its value, and youth unemployment skyrocketed. Years later, Lebanon is still in economic freefall, illustrating how default in the current global system can impact current and future generations.

Tunisia

This North African country has a young population and high youth unemployment. After a 2011 revolution, Tunisia borrowed heavily hoping to boost its economy. Instead, multiple shocks pushed it to crisis. In 2023, Fitch Ratings downgraded Tunisia’s credit rating deep into “CCC” (near default) amid fears it can’t meet its financing needs. Caught between harsh austerity demands and lack of affordable credit, Tunisia is struggling to import basic medicines and food, exemplifying the no-win situation for young countries in debt distress.

Timeline

From Monterrey to FfD4 – Promises Made and Missed

Global leaders have long acknowledged these problems and have made numerous commitments to fix the financial system for developing countries. How have those promises fared? Here’s a timeline of major Financing for Development (FfD) agreements since 2002 and what became of them:

2008

Doha Declaration

In late 2008, a follow-up conference in Doha reviewed Monterrey’s implementation. It basically reaffirmed the Monterrey Consensus and urged donor countries to fulfill their aid pledges despite the unfolding global financial crisis. At the time, developing nations were frustrated by unkept promises – the world had seen G8 countries miss about $30 billion in aid pledges made just a few years earlier. Indeed, the Doha Declaration noted concern that aid levels were still insufficient. Unfortunately, the 2008 global financial meltdown shifted attention and many developed nations tightened their belts. The aid shortfalls persisted (aid to the poorest countries actually fell in subsequent years), and systemic issues like poor commodity price stability and debt relief saw only limited action.

2015

Addis Ababa Action Agenda

Ahead of adopting the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, governments met in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia for the Third FfD conference. The Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) laid out an ambitious plan to finance the SDGs – including domestic resource mobilization (e.g. improving tax collection), calls to curb illicit financial flows, expanding multilateral development bank lending, and leveraging private investment. The outcome was described as a “historic” plan to overhaul global finance and foster inclusive prosperity. However, Addis brought no major new funding commitments from the developed world and mostly repackaged existing goals. Crucially, proposals by developing countries for a more democratic global tax body were blocked, with many countries remaining dependent on volatile private flows.

2025

FfD4 (Fourth Conference, Seville)

The world is now gearing up for the fourth Financing for Development summit, scheduled for mid-2025 in Seville, Spain. Branded “Financing Our Future”, FfD4 is billed as a unique opportunity to finally reform international financial architecture . The conference aims to address the debt crisis, climate finance, and the chronic shortfalls in development funding. There is hope that long-overdue changes – such as debt relief mechanisms, rebalanced IMF voting shares, fair tax cooperation, and scaling up finance for sustainable development – will be agreed upon. The stakes are high: without concrete action, the injustice that young countries have endured since Monterrey will continue, undermining the global goals for 2030 and beyond.

A Call to Action: Youth Demanding Financial Justice

Today’s young generation has the most to gain from fixing the global financial system – and also the most to lose.

As we approach FfD4 in 2025, youth voices are increasingly calling for financial justice and equality. We don’t have to be passive victims of a rigged game. Around the world, young people are organizing for debt cancellation, climate financing, fair tax rules, and greater representation in economic decision-making. They are speaking up on social media with campaigns like #FinanceTheFuture and engaging with global leaders to demand change.

If you’re a young person, what can you do? Get informed and raise your voice. Learn about these issues and how they impact your community. For example, check out the FfD4 Explainers, which break down complex global finance issues in youth-friendly ways. These resources empower young people to understand topics like the debt trap, tax dodging, and aid promises, so we can advocate effectively. Join or support youth-led organizations pushing for reform – whether it’s attending virtual events or even organizing a discussion at your school or university about why global finance matters for your future.