Futures Thinking

Reimagining the Global Economy in 2050

What if global financing was designed for equity, sustainability, and intergenerational justice?

In this article, we time-travel to the year 2100 to explore two speculative futures for our global economy.

Each scenario – from dystopian to optimistic – is grounded in trends from 2020–2024 and mixes imaginative narrative with real policy analysis. The goal is to spark futures thinking about how today’s financial choices shape the world young people will inherit. Let’s dive into the three scenarios:

“Too Little Too Late”

It’s 2100 in the “Too Little Too Late” world – a future that followed our current trajectory without bold change. The scene is grim: inequality has become extreme, many nations stagger under debt, and climate shocks are part of daily life. Mega-corporations and billionaire elites dominate the economy. In fact, way back in 2024 the richest 1% already held more wealth than the bottom 95% of humanity combined, and this gap only widened through the century. Global South countries, home to 79% of the world’s population, entered the late 21st century owning barely 30% of global wealth – a stark legacy of an unjust financial system.

By the 2070s, debt crises cascaded across developing economies. This too had roots in the 2020s: in 2023, about 60% of low-income countries were already in or at high risk of debt distress. In our 2100 dystopia, that figure hit nearly 100%, forcing governments to choose between serving creditors or their citizens. Public services withered as debt payments ate up budgets, reminiscent of how interest costs for the poorest nations quadrupled in the 2010s. The “debt trap” became practically inescapable.

Meanwhile, the climate crisis rages unabated. Decades of insufficient action led to a planet ~2.7°C hotter by 2100 – exactly what scientists in 2024 warned would happen under current policies. The consequences are devastating: more intense floods, droughts, and storms pummel communities worldwide. Back in the 1970s-2010s, the number of weather-related disasters had already increased fivefold due to global warming. By the end of this century, in our “too late” scenario, climate disasters are even more frequent and ferocious, pushing vulnerable societies beyond their limits. The toll is heartbreaking: millions displaced by superstorms and rising seas, and economies knocked into permanent recession by recovery costs. The lack of early climate action also meant higher long-term costs – a tragic echo of the fact that wealthy countries only met their $100 billion climate finance pledge two years late in 2022, far short of the trillions needed to protect communities. In 2010, the bill for inaction came due, with the poorest and youngest paying the steepest price.

This future is a warning. It shows what might happen if we continue business-as-usual: growing inequality, unsustainable debts, and an escalating climate crisis – truly too little, too late. But it doesn’t have to be this way. Let’s explore a radically different 2100.

“The Giant Leap”

Now imagine “The Giant Leap” – an alternate 2100 where, early on, humanity chose equity, sustainability, and justice. In this hopeful future, the world implemented bold reforms in the 2020s and 2030s that reshaped global finance for the better. The results by 2100 are extraordinary: poverty has plummeted, clean energy powers the planet, and economies are more equal and resilient. How did we get here?

It began with courageous policy leaps. Nations came together to pursue global tax justice. Back in the 2020s, there was growing outrage that nearly half a trillion dollars in taxes were being lost each year to loopholes and tax havens – money that could have funded schools, hospitals, and green infrastructure. In our Giant Leap scenario, governments struck a global deal to make the richest pay their fair share. Tax havens were reined in, a 15% minimum corporate tax was adopted worldwide, and new wealth taxes ensured billionaires contributed to society. By 2100, these measures unlocked huge revenues that were invested in sustainable development. For example, instead of losing an estimated $4.8 trillion to tax dodging in the 2020s-30s, that money was redirected to climate solutions, education, and healthcare. The effect was transformative – inequality gradually declined as every country had resources to lift up the poor and invest in the future.

At the same time, the world embraced climate justice on a global scale. Wealthy countries finally acknowledged their historical responsibility for emissions and made reparations to climate-vulnerable nations. A key turning point was the establishment of a Loss and Damage Fund in 2022 – a fund to help poorer countries recover from climate disasters . In the Giant Leap timeline, this fund wasn’t just a token gesture; it grew into a robust mechanism channeling hundreds of billions of dollars by mid-century to hard-hit regions for rebuilding and adaptation. Developed economies rapidly scaled up climate finance, far beyond the long-stalled $100B goal. They directed grants (not loans) to developing countries, recognizing that saddling them with more debt to address a crisis they didn’t cause was unfair. This investment paid off: by 2100, renewable energy and green jobs flourished everywhere, and communities worldwide were better protected against storms and droughts. Global temperature rise was kept to about 1.5°C, avoiding the worst-case climate scenarios. In essence, the world made a giant leap in treating our atmosphere and each other with justice – ensuring future generations inherit a livable planet.

Another pillar of this optimistic future was equitable financial governance. The international financial institutions – like the IMF and World Bank – underwent dramatic reforms to give developing countries a stronger voice and fairer terms. In the 2020s, calls for a more inclusive financial system grew louder; even the UN Secretary-General urged a 500 billion $per year stimulus to support developing nations and fix the “great finance divide” . Under the Giant Leap, these reforms happened. Unpayable debts were forgiven or restructured, freeing countries to invest in their people instead of paying interest to wealthy creditors. New rules prevented predatory lending and ensured emergency funds were available when crises hit. Imagine a world where no country has to choose between servicing debt and serving its citizens – that’s the reality in 2100’s Giant Leap scenario. Global institutions prioritize long-term sustainability and shared prosperity, reflecting the principle of intergenerational justice – we don’t achieve growth today by stealing from tomorrow.

All these changes required courage, cooperation, and the insistence of informed citizens (like youth activists pushing for climate and economic justice). The payoff in 2100 is a world that, while not perfect, has mitigated the worst inequities and averted climate catastrophe. It’s a future where the global economy is finally aligned with human rights and ecological balance. As fantastical as it may sound, every element of this scenario is rooted in real ideas already on the table – from tax reforms to climate funds – showing that a giant leap is possible if we choose it.

Visualizing the Stakes Ahead

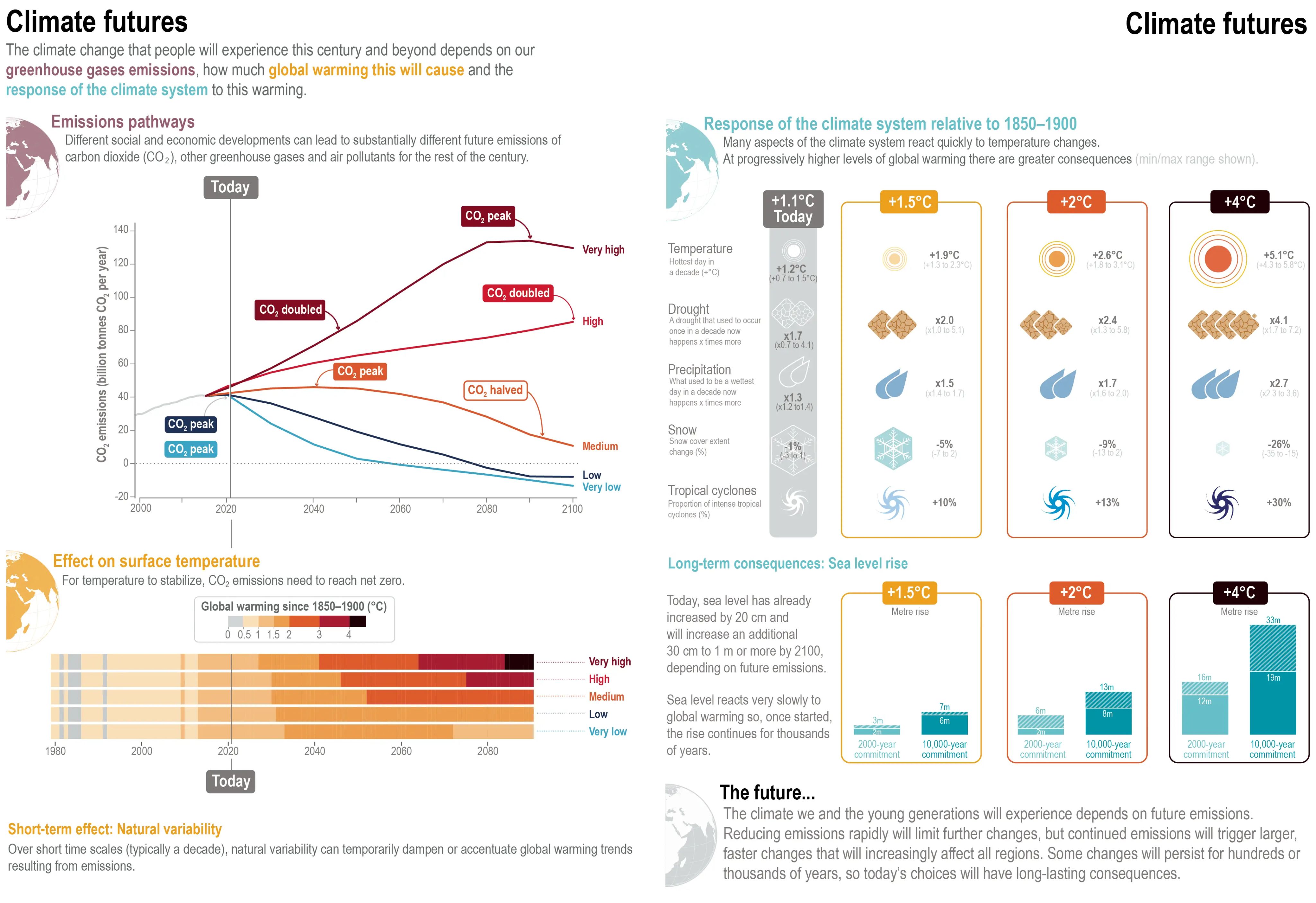

The IPCC’s “Climate Futures” infographic shows how our choices today lead to very different outcomes by 2100. Under the highest emission scenario (red), CO₂ emissions double and global warming exceeds +4°C, bringing extreme increases in temperature, droughts, heavy rainfall, and sea level rise; under a very low scenario (blue), emissions peak now and fall to net-zero, limiting warming to about +1.5°C . The difference is dramatic – for example, a +4°C world could see tropical cyclones intensify and precipitation extremes become 1.7 times more frequent, whereas a +1.5°C world sees more moderate changes . This visualization makes clear that by 2100, climate impacts will vastly diverge depending on the path we take.

Infographic TS.1 in IPCC, 2021: Technical Summary. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Chen, D., M. Rojas, B.H. Samset, K. Cobb, A. Diongue Niang, P. Edwards, S. Emori, S.H. Faria, E. Hawkins, P. Hope, P. Huybrechts, M. Meinshausen, S.K. Mustafa, G.-K. Plattner, and A.-M. Tréguier, 2021: Framing, Context, and Methods. InClimate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 147–286, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.003.]

Infographic TS.1 in IPCC, 2021: Technical Summary. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Chen, D., M. Rojas, B.H. Samset, K. Cobb, A. Diongue Niang, P. Edwards, S. Emori, S.H. Faria, E. Hawkins, P. Hope, P. Huybrechts, M. Meinshausen, S.K. Mustafa, G.-K. Plattner, and A.-M. Tréguier, 2021: Framing, Context, and Methods. InClimate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 147–286, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.003.]

Your Turn: Shaping the Future of Finance and Justice

Futures thinking isn’t about predicting exactly what will happen by 2100 – it’s about understanding that the world we leave to the next generations is actively shaped by our decisions today. As young people, you have a critical voice in this process. The scenarios above are like sketches; the final picture of 2100 will be colored by activism, innovation, and leadership, much of it coming from the youth. Whether it’s campaigning for climate action, pushing for fair economic policies, or using your skills to drive sustainable innovation, every action counts.

The year 2100 might feel a long way off, but the journey to that future is being mapped now. Will we allow “Too Little Too Late” to happen, or will we leap toward justice? The hopeful news is that momentum for change is growing – from youth climate strikes to movements for debt relief and tax fairness – and you can be part of it.

- Start by educating yourself and others using FfD4 Explainers. Share infographics and stories about these issues.

- Get involved in the Engine Room for the Future to join local and global campaigns for climate justice, tax justice, and inclusive governance.

- Vote with these principles in mind, if you can, and hold leaders accountable.

Perhaps most importantly, imagine the future you want to see – like we did here – and then work with your peers to make it reality. The global economy of 2100 is not predetermined; it will be the sum of countless choices made by people like you.

So let’s choose wisely, demand boldly, and ensure that the future of finance and justice is one we’ll be proud to gift to the next and future generations.